While driving home from the airport, Lurene notices a crowd has gathered around a television set in a shop window. Then, a few police cars race past her. Sensing something terrible has happened, Lurene pulls over to investigate, only to learn that her beloved President has been gunned down, and is dead.

Distraught, Lurene announces to her husband Ray (Brian Kerwin) that she plans to travel to Washington D.C. to attend the President’s funeral. Ray forbids it, and tells Lurene in no uncertain terms that she is to stay home and get on with her life. Angry and determined, Lurene packs a bag and sneaks out that night, hopping a bus headed north.

While on the road, Lurene strikes up a conversation with Paul Cater (Dennis Haysbert), an African American who is traveling with his mute daughter Jonell (Stephanie McFadden). Mistaking Paul’s secrecy and Jonell’s failure to talk, along with some bruises on the young girl’s body, as a sign the she has been taken against her will, Lurene sneaks into a rest stop pay phone and alerts the FBI.

But the truth is very different.

Paul is, indeed, Jonell’s father, and has been living in Philadelphia. After her mother died, Jonell was placed in an orphanage, where she was abused. To save his daughter from a very bad situation, Paul snuck Jonell out and intends to bring her north with him, where she has a chance at a better life.

Regretting her actions, Lurene agrees to accompany Paul (who now had to steal a car to get back on the road) as far as Washington D.C., doing what she can to help them dodge the Feds (who are hot on their trail) before hopping out to attend the President’s funeral.

During their journey, Lurene’s and Paul’s eyes will be opened to the realities of life in 1960’s America, as well as the possibility there might be something more out there for both of them

The opening scenes of Jonathan Kaplan’s Love Field center on the Kennedys’ arrival in Dallas and the President’s subsequent assassination, and get the movie off to a dramatic start. The scene where Lurene discovers what has happened is one of the film’s most poignant, and is handled to perfection by Pfeififer, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her performance here.

Love Field also shines a light on bigotry, with Lurene, who up to that point believed President Kennedy had improved things for African Americans, realizing not much has changed after all. At the first rest stop, Jonell needs to use the bathroom, only to find the “colored” toilet is out of service (it’s the only one blocked off). Later, as the three drive the highways of the south, Paul will incur the wrath of a truckful of rednecks, who want to know why he’s traveling with a white woman.

Yet, at its heart, Love Field is neither an account of an American tragedy or an exposè on the injustices of racism. Both are there for the taking, and are presented quite well by director Kaplan, screenwriter Don Roos, and the film’s fine cast. But this is a love story, in which two people from very different backgrounds find each other, and under extreme circumstances fall in love.

In one very memorable scene, Lurene, Paul, and Jonell are hiding out at the house of Mrs. Enright (Louise Latham), the mother of Lurene’s boss. A police car approaches, and the cop asks Lurene (who went out to meet him) if she has seen Paul. As Paul is hiding in an upstairs bedroom, he hears Lurene tell the officer she has not seen him, then uses a racial slur to further throw the police off the trail.

Hearing Lurene use this word is shocking for the audience. Her racism up to that point stemmed more from ignorance, and the mistaken belief things have improved for African Americans.

As shocking as it was for us to hear Lurene say this word, it was doubly so for Paul. During the journey, he experienced racism and hatred at nearly every turn, yet never protested or fought back, so that he could get his daughter to safety without drawing attention. Yet he reacts angrily to Lurene’s slur, and announces he is taking his daughter and leaving. It’s clear at this point he couldn’t care less what the rest of the world thinks, but to hear Lurene, who he has grown to care for, talk that way has hurt him.

But here’s the thing: he knew why she did it! She said it to get them out of a jam. Paul realizes that, yet cannot hide his heartbreak. It’s a clear sign that a deeper relationship has developed between the two than either of them realized.

Much like 2002’s Far from Heaven (which also featured Dennis Haysbert as Julianne Moore’s eventual romantic interest), Love Field tells a tale of love across racial lines, and during one of the most chaotic periods of American history. Thanks to the fine work of all involved, it does so wonderfully.

Rating: 9 out of 10

She’s absolutely right, because as good as Hunt, Matthew Broderick, William Sadler and the remainder of the cast is in Project X, it’s the chimps who steal the show.

Hunt plays Teri MacDonald, a University of Wisconsin grad student who, for her thesis, is attempting to prove that chimpanzees can communicate with sign language. After only a few months working with her test subject, Virgil (played by Willie), she has a breakthrough, and the two are communicating freely. That is, until Teri’s funding is cut off, at which point the University informs her Virgil is om his way to a children’s zoo in Houston.

But that’s not the case. Instead, the clever chimp is shipped off to an Air Force base in Florida, where, teamed with troublemaking Airman Jimmy Garrett (Broderick), Virgil becomes one of many test subjects. The program, headed up by Dr. Carroll (William Sadler), uses flight simulators to determine if chimps can be trained to fly, and, if so, how they perform under certain conditions.

It isn’t long before Jimmy realizes there is something special about Virgil, and that an Air Force research facility is no place for such a gifted chimp, especially once he learns what happens when a so-called gifted chimp “graduates” to the next level.

Project X is, in many ways, a standard ‘80s comedy / drama, touching all the bases story-wise that you would expect. Yet it has a few things going for it, which lift the movie a level or two above the rest. First is the fine work of its cast, both human and primate. Released in 1987, Project X caught Matthew Broderick in his cinematic prime, having already won the hearts of audiences with WarGames and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. He is every bit as likable in this movie, as is Helen Hunt as the dedicated scientist who comes to love her test subject. On the other side of the coin is William Sadler as the cold, calculating military scientist whose experiments have one natural conclusion.

Then there are the chimps, led by Willie, whose Virgil is, without question, the film’s most endearing character. We follow Virgil on his entire journey, from being captured in the wild to his time with Teri, straight through to Jimmy and the Air Force. As such, we already know how gifted Virgil is, and part of the fun is watching Jimmy figure it out as well. There are other chimps in the film, each with their own distinct personality, and we find ourselves rooting for them as much as we do Teri and Jimmy.

All leading up to the film’s final act. Based on the general tone throughout, you can pretty much guess what kind of ending Project X is going to have, yet the journey there is chock full of surprises, moments I would never have predicted, including an ending so outlandish that you could only find it in a Hollywood movie.

But then Project X is a Hollywood movie, and because we like the characters, it wins us over, no matter how over-the-top or unlikely it’s grand finale might be. I knew it was ludicrous, but I was smiling anyway.

Rating: 8 out of 10

Yet as good as Dillon is, what stayed with after watching this 1979 film was my reaction to its story, which was not the reaction I was anticipating. Set in the brand new, isolated suburban community of New Granada, Over the Edge approaches juvenile delinquency and teen violence not as a problem that needs to be dealt with, but (in this case, anyway) the natural progression of what occurs when parents, to make a better life for themselves and their families, fail to consider the effect it will have on their kids. Cut off from the world, these youngsters have nothing to do, and stirring up trouble is their way of dealing with the sheer boredom of it all.

Carl Willat (Michael Kramer), one of the many teens residing in New Grenada, comes from a good home. His father (Andy Romano) owns a successful car dealership, and his mother (Ellen Geer) loves Carl unconditionally. Yet, despite a seemingly stable home life, Carl has fallen in with a crowd of “troublemakers”, including Richie White (Dillon), Claude (Tom Fergus), and Cory (Pamela Ludwig), on whom Carl has a crush.

Carl’s father is particularly annoyed at his son’s behavior, which includes being hauled to the police station with Richie by Sgt. Doberman (Harry Northup), who is convinced the two shot a BB gun into the window of his squad car (it was actually done by another teen, Mark Perry, played by Vincent Spano).

Though forbidden to hang out with Riche and the others, Carl and his friends continue to stir up trouble, attending an after-hours party and firing a gun that Cory and her friend Abby (Kim Kliner) swiped from a nearby house.

When the vandalism and lawlessness costs the community some possible investors, who were looking to put up a strip mall, homeowners association president Jerry Cole (Richard Jamison) and Sgt. Doberman enact a curfew, and even go so far as to shut down the local rec center run by Julia (Julia Pomeroy), the only place where the kids can blow off a little steam.

But it’s a sudden and unexpected tragedy that will push the teens “over the edge”, causing them to lash out in a way nobody would have dreamed possible.

Kramer and especially Dillon deliver strong performances as kids dealing with the monotony of their secluded community as best they can. The rec center where they and their friends hang out is nothing more than a makeshift garage with a few games for them to play. Yet it is always overcrowded; every kid is there just about every day because it’s all they have.

They are continually harassed by the police. In one very tense scene, Sgt. Doberman strolls into the rec center and, ignoring Julia’s protests, arrests Claude for drug possession, causing a near-riot when he tries to lead his new prisoner out of the center and into his squad car.

Kaplan and screenwriters Charles Haas and Tim Hunter do a fine job bringing us not only into the world of these teens, but their mindset as well. They are restless and fed up, and mayhem is all they have to keep from losing their minds. Even a glimmer of hope, the promise of a movie theater and skating rink, is taken from them when the homeowners association decides to use that land for the potential strip mall instead!

Being a father of two adult kids, I’m now of an age where, if I’m not siding with the parents in Over the Edge, I should at least commiserate with them. And I do, to a degree. But their lack of understanding when it comes to their kids’ so-called delinquency frustrated the hell out of me. Carl’s parents do eventually come around (spurred on by Carl running away from home and hiding out for days in a partially-constructed home he and the other kids use as a hangout), and his father even speaks up at a hastily called parents meeting, to address the growing problem. But by then, it’s too late. The kids have reached their breaking point, and put in motion an elaborate and even dangerous plan to get back at the adults once and for all.

As I said, I understood the parents to a degree, but I was team kids all the way, and actually rooted for them during the film’s shocking conclusion.

Rating: 9 out of 10

“In cinema, as in life”, Klimov said in a 1986 interview, “the atmosphere changes very fast. In movies, styles change fast, too. If a film is not released immediately, it soon dates. It loses its relevance to new thoughts, new ideas. If a film is not released for 10 years, it’s a real tragedy”.

The fact that Agony remained out of circulation for so many years was, indeed, a tragedy, but not the disaster it would have been had it stayed on that shelf permanently. Infusing the movie with a unique, occasionally flashy style, Klimov gives us a story of Rasputin unlike any we’ve seen before.

The year is 1916, the waning days of Imperial Russia. Grigori Rasputin (Aleksey Petrenko), a Siberian-born mystic and self-proclaimed Christian monk, has stirred up quite a bit of trouble with his role as trusted advisor to Tsar Nicholas (Anatoliy Romashin) and especially his wife, the Tsarina Aleksandra Fyodorovna (Velta Line). A drunkard and a womanizer, Rasputin was the source of a number of scandals, at one point even advising the Tsar to change military tactics in time of war, resulting in a terrible defeat for the Imperial army.

Government and religious leaders alike denounced Rasputin, but it was an assassination plot devised by several men, including Prince Felix Yusupov (Aleksandr Romanstov), Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich (Sergei Muchenikov), and politician Vladimir Purishkevich (Yuriy Katin-Yartsev), that finally ended Rasputin’s reign of terror. As the conspirators soon discovered, however, it would take more than poison and a few bullets to bring this “Holy Man” to his knees!

With a baroque, lively approach to the material, Klimov engages us on an emotional level throughout Agony, from anger and revulsion at Rasputin’s actions (at a party one evening, he sexually assaults a Baroness played by Nelli Pshyonnaya) to pity and a hint of admiration for Tsar Nicholas, portrayed throughout the movie as a weak but basically decent guy (one of several issues Soviet authorities had with the film). Romashin and especially Line deliver strong performances as the Tsar and Tsarina who have fallen under Rasputin’s spell, and Alisa Freindlich is also quite good as Anna, Rasputin’s cohort and chief confidante. But it is Petrenko who steals the show, playing Grigori Rasputin as a loathsome opportunist and even a sexual deviant. The Baroness he accosted at the party eventually submits to Rasputin’s sexual advances to protect her husband, who was arrested for trying to defend her honor.

Along with its cast, Agony is a stylistically engaging motion picture. Klimov brings a vivacious, almost comedic energy to a number of scenes, letting his creativity run wild at several points throughout the film, culminating in the movie’s strongest sequence: the assassination of Rasputin, depicted here in a manner that is both historically accurate and incredibly tense (much to the chagrin of his assassins, Rasputin refused to die quickly).

As with Come and See, Agony is not an easy film to watch, but you will be doing yourself a disservice if you miss either.

Rating: 9.5 out of 10

Parajanov’s most notable film, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, broke socialist boundaries in every way imaginable: story, theme, execution, and style, and in so doing became one of the most important motion pictures of the 1960s.

Set in a small Hutsul village in Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors tells the story of Ivan (Ivan Mykolaichuk). As a young boy, Ivan witnessed the murder of his father Petrik (Aleksandr Gai), who was beaten to death by Onufry (Aleksandr Raydanov), who Petrik had insulted. Despite the bad blood between their families, Ivan would eventually fall in love with Onufry’s daughter Marichka (Larisa Kadochnikova), whose feelings for him ran just as deep.

To earn money so he could marry Marichka, Ivan leaves their village to seek employment. While he was away, Marichka accidentally drowned trying to save a lost lamb.

Though heartbroken, Ivan would eventually fall in love with Palagna (Tatyana Bestayeva). The two marry, but over time Ivan becomes distant, unable to forget his love for Marichka, and it isn’t long before Palagna is having an affair with Yurko (Spartak Bagashvili).

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors stood apart from most by being one of the few Soviet-era films in which the characters spoke Ukrainian instead of Russian. Yet this 1965 movie would also distinguish itself in ways beyond the spoken word. Turning his back on the Soviet socialist realism mandate, Parajanov relied heavily on symbolism, both religious and cultural, throughout the movie; we are treated to traditional weddings, funerals, and holiday celebrations, complete with all their customs. There is plenty of folklore as well, mostly religious in nature. Lambs are a recurring theme throughout the movie, and a dream sequence centers almost entirely on the cross of Jesus. There’s even a chapter titled “Sorcery” that delves into the supernatural.

Parajanov infuses the film with style to spare. As Petrik faces off against Onufry, the camera swings around to a POV shot, so that we are suddenly seeing the action through Petrik’s eyes. When Onufry strikes Petrik, blood flows across the screen. The scenes where Ivan is in mourning for Marichka are shot in black and white, to convey his mood, only to be replaced by color once again when he meets Palagna. There is music as well, including a late sequence in which Ivan sings a duet with the spirit of Marichka.

By continually blurring the line between reality and fantasy, and doing so with such artistry, Parajanov did more than turn his back on Soviet restrictions; he took the art of film in unique, exciting new directions. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors stands alongside Battleship Potemkin, Andrei Rublev, and Come and See as one of the greatest movies to emerge from Soviet Russia.

Rating: 10 out of 10

Starting in February of that year, when the new Government first came into power, October then highlights the events leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution, from the arrival of Vladimir Lenin (played by Vasili Nikandrov) at the Petrograd Railway Station to the July massacre of protesting Bolsheviks in Nevsky Square.

With the Provincial Government both incompetent and corrupt, the Bolsheviks gained in popularity, winning favor with the people and the military, all leading up to those fateful days in late October 1917, when Socialist Russia was born.

Along with being a staunch supporter of the Bolshevik regime (he fought with the Red Army during the revolution), Sergei Eisenstein was also a well-respected film theorist and a proponent of the practice of montage, a technique by which a series of seemingly unrelated shots are edited together to tell a story, introduce symbolism, and establish a rhythmic flow. Eisenstein’s reliance on montage went a long way in making his 1925 film Battleship Potemkin an undisputed cinematic classic. Unfortunately, his quick-cut style and sharply contrasting imagery proved more hit and miss in October, and at times even drained the energy from it.

Eisenstein’s rapid editing works well in October’s “big” scenes, like the opening, when an angry mob topples a statue of the Tsar, as well as Lenin’s arrival in Petrograd. It is especially effective in the Nevsky Square sequence, where Bolsheviks were fired upon by the army as they marched through the streets (the Provincial Government ordered a bridge raised to prevent the Bolsheviks from advancing, leading to several unforgettable images when the bodies of the recently killed slide down as the structure gets higher).

Alas, the quick cuts undermine some of the movie’s more serene moments; a scene in which soldiers enjoy a few minutes of camaraderie on the battlefield features so many individual shots that it quickly becomes a distraction. I would venture to guess there isn’t a shot in this sequence that’s more than 2 seconds in length!

While I admire Eisenstein’s commitment to technique, and agree that montage, when used efficiently, can do wonders to further a movie’s story, less “technique” and more “story” would have made October a much better film.

Rating: 6 out of 10

I have always heard this particular ritual was symbolic, a way to put each and every man, regardless of race or background, on an even playing field. They are no longer individuals, and before long they won’t even have a name anymore. Just a nickname, assigned to them by their bombastic drill instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played to perfection by R. Lee Ermey (in part because, as a former Marine drill instructor in real life, he was essentially playing himself).

Among the raw recruits Hartman must mold into finely-tuned soldiers are Joker (Matthew Modine), Cowboy (Arliss Howard), Snowball (Peter Edmund), and the dim-witted Private Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio, in what is undoubtedly one of the greatest screen debuts in cinematic history).

Hartman is merciless in his approach to their training, especially where Pvt. Pyle is concerned. Overweight and a little slow, Hartman works on Pyle, insulting him at every turn, and humiliating him when he cannot complete the obstacle course. When Pyle continues to foul up, Hartman changes tactics by punishing the entire platoon. If he cannot motivate Pyle, then maybe incurring the wrath of his fellow recruits will do the trick (in one of the film’s most disturbing scenes, the squad does take its anger out on Pyle after lights out).

Pyle eventually falls into place, and becomes like everyone else. But his psyche has been shattered. Hartman’s goal at the outset was to break every man down and build them up again, into a team, proud members of the United States Marine Corps. The tale of Pvt. Pyle is what happens when a broken man cannot be rebuilt, and his story stands as the first act of Kubrick’s masterwork, a film as much about the mentality of war as it is about war itself.

Now that the recruits have been prepared for life in the Marine Corps, it is off to war. Most are assigned to infantry units in Vietnam, but Pvt. Joker, who occasionally acts as the film’s narrator, fancies himself a writer, and joins the staff of Stars and Stripes. He is assigned a photographer, Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard), and writes stories that reflect favorably on the U.S. war effort.

That changes, however, after the Tet Offensive, when the Viet Cong breaks a peace treaty during the country’s New Years’ festivities and hands the Americans a handful of crippling defeats. With things looking bleak for the U.S., Joker and Rafterman are re-assigned to field duty, to tag along with a platoon of Marine grunts and report on their progress.

By chance, Joker is sent to the unit of his old buddy Cowboy, who, along with fellow Marines Eightball (Dorian Harewood), Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), and Lt. Touchdown (Ed O’Ross), are sent to a deserted village to verify reports that the enemy has retreated, only to find themselves facing off against a very skilled sniper.

So, that’s the story that makes up Full Metal Jacket, but it doesn’t scratch the surface of what Kubrick and his team accomplish with this movie.

The second half of the film, which centers on the war itself, is skillfully shot, with fluid handheld shots that follow the Marines as they carry out their orders, moving from one life-threatening situation to the next. These scenes are punctuated by the film’s haunting score (created by Vivian Kubrick, under the alias Abigail Mead), which keeps the audience on edge, always at the ready for something to happen.

The cast is equally superb, with Matthew Modine leading the way as the complex Joker; he wears a peace symbol on his uniform, but has “Born to Kill” written on his helmet. Because we spend more time with him than any other character, Modine's Joker is essentially the lead. But every individual gets a moment in the sun, and is given a chance to strut their stuff. And they all make the most of the opportunity (especially D’Onofrio and Adam Baldwin, who more than earns his character's nickname "Animal Mother").

The sets are well-realized, the action scenes are impeccably staged, and the inherent drama of the basic training sequences builds the tension to an almost unbearable level.

But then, when it comes to Kubrick, we know the physical aspects of a film will be flawless. He was a perfectionist, doing as many as 30-40 takes of a scene, until he, and his cast and crew, got it right. To call Full Metal Jacket a stunning technical achievement is not newsworthy. Kubrick would have never released it were it not so.

What it comes down to, then, is the film’s central theme, and how Kubrick and his team convey it: the effect of not only war, but the preparation for war on the individual, as seen through the eyes of men whose individuality has been stripped away. Kubrick could have easily made some grand statement here, damning the loss of one’s identity, or the impact that uncertain death can have on a man’s psyche. There are traces of both here, but more than anything, it is about the attitude of the soldier, who knows he could die at any minute yet performs his duties without question.

There is no cowardice to be found in Full Metal Jacket, no hesitation in carrying out orders, regardless of how dangerous they might be, or their ultimate consequences. Kubrick’s fascination, as I see it, was with the mindset of soldiers in the midst of war, who, surrounded by enemy combatants attempting to kill them, somehow throws caution to the wind to serve their country. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman’s job was to turn men into killing machines, and Kubrick shows us time and again during the Vietnam sequences that he and his fellow drill instructors managed to do exactly that.

I saw Full Metal Jacket during its initial run in 1987 with my father, who is himself a Vietnam veteran. He had been critical of some Vietnam-themed films in the past, saying he found Apocalypse Now “weird”, and Platoon a little too over-the-top. During the initial scenes of Full Metal jacket, I sat there and wondered what his reaction to this movie was going to be.

As the story played out, though, I realized that Kubrick had pulled me into his film completely, to the point that, when the end credits did finally roll, my father’s opinion was no longer my primary concern. I knew I had just seen a masterpiece, and that was all that mattered.

Rating: 10 out of 10

The above quote has been attributed to Jack Nicholson, the star of Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film The Shining. But Nicholson could have just as easily been referring to the great director’s 1975 opus Barry Lyndon.

Time and again, Kubrick frames his shots in Barry Lyndon like they were a work of art, as if his audience was walking through a vast gallery of history’s finest paintings. He starts in extreme close-up, with the one image that would undoubtedly catch our eye were it framed and hanging on a wall: his lead character chopping wood, or a British regiment on parade. Then, his camera slowly pulls back, revealing the spectacle, the grandeur of the surrounding landscape.

His framing of each and every scene in Barry Lyndon is measured. It is deliberate. It is… meticulous.

Based on the 1844 book The Luck of Barry Lyndon by William Makepeace Thackeray, Barry Lyndon relates, in two distinct sections, the rise and fall of notorious opportunist Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal), a common Irishman who, in the 1700’s, would rise to the rank of an English aristocrat.

Following a duel with British army captain John Quin (Leonard Rossiter), the fiancé of his cousin and first love Nora (Gay Hamilton), a young Redmond Barry flees to Dublin, where he joins the army of King George. When his close friend Grogan (Godfrey Quigley) is killed in a skirmish during the Seven Years War, Redmond deserts his post, only to be apprehended by Captain Potzdorf (Hardy Krüger) of the Prussian military.

Thus begins a series of events that, over time, will see Redmond Barry hook up with notorious gambler the Chevalier du Baribari (Patrick Magee), and marry Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson), widow of Sir Charles Reginald Lyndon (Frank Middlemass).

Having achieved an air of respectability, Redmond Barry behaves like a brute, cheating on his new wife while at the same time spending her entire fortune. This causes a rift between Redmond and his stepson Lord Bullington (played as an adult by Leon Vitali), one that grows larger, and more venomous, with each passing year.

Barry Lyndon is, without question, a beautiful motion picture. There are scenes as gorgeous as any ever captured on film. This polished presentation has been attacked by the movie’s detractors, who claim the film is all style and no substance, with little or no story. But I cannot agree. There was never a moment in the movie where I wasn’t engaged by the tale of lead character Redmond Barry, whose antics fall more in line with those of an anti-hero than a hero.

Barry aligns himself with the Chevalier du Baribari, who, in reality, is an Irishman much like himself, posing as a European aristocrat. Aided by Barry, the Chevalier cheats at cards and other games of chance to gain the upper hand on his wealthy opponents. Barry’s motivations become even more suspect later in the film, after he marries Lady Lyndon. At this point in the movie, Barry isn’t even an anti-hero; he is a straight-up villain, ignoring his wife and mistreating Lord Bullington, her son from her previous marriage. And yet we, the audience, are still somehow drawn to Barry. We find ourselves siding with him against his stepson, who, though in the right, is never as magnetic a personality as his unscrupulous stepdad.

It is difficult to pinpoint a single moment in Barry Lyndon when Redmond Barry is entirely likable. Even in the early scenes with his cousin Nora, Barry comes across as course and naïve. But we are engaged by his exploits all the same.

While it is unjust to categorize Barry Lyndon as a totally stylistic affair, it is, admittedly, Kubrick’s visuals that draw you in, the gorgeous shots littered throughout the film that make it a masterpiece. Kubrick may, indeed, have been a perfectionist, but he put that particular skillset to good use throughout this movie.

Barry Lyndon is a measured, deliberate, meticulous tour de force.

Rating: 10 out of 10

Sitting down to watch Stanley Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss, his second feature (his first, Fear and Desire, was withdrawn by Kubrick himself, who wasn’t happy with the final result), had me wondering if I might see early shades of the master director’s noted style peeking around the corners of this 1955 film noir. Would there be traces of the “Kubrick Touch” that, in later years, would transform Paths of Glory, 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, and others into bona-fide cinematic classics?

Well, one thing about Killer’s Kiss was certainly true to form for the great director; the answers to these questions aren’t nearly as cut-and-dry as I was hoping!

Washed-up boxer Davey Gordon (Jamie Smith) lives in a rundown apartment in New York City. Across the alley from him resides Gloria Price (Irene Kane), a taxi dancer whose boss, Mr. Rapullo (Frank Silvera), won’t leave her alone (he claims to have fallen madly in love with Gloria). One night, after hearing Gloria scream for help, Davey runs to the rescue, kicking off a whirlwind romance between the two.

But when Davey and Gloria decide to leave town together, they find out pretty quickly that crossing the jealous Rapullo can be hazardous to their health!

By the time he made Killer’s Kiss, Stanley Kubrick had already established himself as one of New York’s most prominent photographers, with his pictures appearing in Look Magazine as early as 1945. By the late ‘40s, Kubrick had become enamored with motion pictures, which would be his profession - as well as his obsession - for the remainder of his life. Yet in Killer’s Kiss, his photographic sensibilities seem to be at the forefront; there are entire scenes set on the streets of New York, where Kubrick - known in later years as a very controlling, meticulous director - simply shot whatever caught his eye, from a pair of performers marching down 42nd Street to the display windows of nearby shops and the trash-lined streets.

To see the man who set a world record by making Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall redo a single scene in The Shining 148 times simply “winging it” in Killer’s Kiss was something of a culture shock. But with his keen eye, what Kubrick did capture on film - in stark, stunning black and white - was something quite extraordinary (especially memorable is a late chase scene, in which Davey is running through desolate back alleys to avoid Rapullo and his cronies).

That’s not to say there aren’t hints of Kubrick the filmmaker to be found throughout Killer’s Kiss; an early scene, where Davey walks through his apartment, impatiently waiting for a phone call (eventually revealing Gloria’s apartment in the background), felt controlled and carefully staged, and the fight sequence, in which Davey faces off against the champion, was shot with a hand-held camera, making the bout as tense as it is exciting.

The performances are decent though not extraordinary (save Silvera, who makes for a fine villain), and plot-wise, Killer’s Kiss is nothing special; aside from a few intriguing flashbacks in which Gloria discusses her father and Ballerina sister (played by Kubrick’s wife Ruth Sobotka) and a thrilling climax set in a mannequin factory, the story that makes up Killer’s Kiss is film noir at its most routine.

But for fans of its director, the chance to see him sharpening his skills while at the same time allowing his photogenic eye to wander make this a movie you won’t want to miss!

Rating: 8 out of 10

Instead of adhering to a lesson plan, high school teacher Peter Gifford (William Shatner) believes in keeping an open dialogue with his students. One day, he asks them all to write an anonymous essay on what it is they are concerned about, - i.e. their future, college, finding a job, etc.

One student, Janet Sommers (Patty McCormack), who the night before was coerced by her longtime boyfriend Dan (Lee Kinsolving) into spending the entire night with him at a party, raises her hand and says the most pressing issue she is facing is sex, specifically, when is it the right time to sleep with a boy? Though understandably reluctant to introduce such a sensitive topic into the discussion, Mr. Gifford relents when a few other students agree with Janet, and also want to write about sex.

What starts as a simple school project soon becomes an all-out scandal when the rumor spreads around town that Mr. Gifford distributed a “sex questionnaire” to his class. The parent / teacher’s association, led by Janet’s mother (Virginia Field), Dan’s father (Phillip Terry), and local businessman Bobby Herman Sr. (Steve Dunne), whose son Danny Jr. (Billy Gray) threw the party that sparked Janet’s query, get together and demand that Mr. Gifford not only apologize, but also turn over the essays written by the kids for “further examination”.

This initiates a showdown, with Mr. Gifford and his students on one side, and school principal Morton (Edward Platt) and the parents on the other.

The Explosive Generation focuses on a number of hot-button topics that are as prevalent today as when it was made 60+ years ago, including teen sexuality, a lack of communication between parents and their children; and an injustice that is often dismissed as being for the “greater good”. First and foremost, this is a well-acted film. Shatner delivers a solid performance as the teacher who has won the respect of his students, and McCormack is also effective as the confused but strong-willed Janet, whose insistence on writing about sex briefly alienates her from her boyfriend Dan (he feared everyone will know why she brought it up in the first place), only to eventually become the rallying cry for her peers, Dan included. Also appearing in a supporting role is a young Beau Bridges, who plays Mark, a friend of Dan’s and Janet’s.

Yet as good as the performances are, it is the subject matter and the inevitable confrontation between teens and adults that will stay with you long after the movie is over. I wouldn’t think a television movie from the 1960s would have dealt with teen sexuality in quite as open a manner, and it’s to the film’s advantage that it tackles it head-on.

While we do occasionally understand the parents and their way of thinking (there is a well-executed scene that features a heart-to-heart between Dan and his dad), I was “Team Kids” every step of the way! Believing they have no choice but to rebel to save Mr. Gifford’s job, they devise a plan, and watching as they put it into action will have you cheering out loud.

Yes, The Explosive Generation surprised me, and because of this it is a movie I recommend without hesitation. It’s not often that a film will catch you as off-guard as this one caught me.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

This is an excerpt from author Rob Burt’s 1983 book Rockerama: 25 Years of Teen Screen Idols, and it touches on what is perhaps the most potent legacy of Richard Brooks’ 1955 movie Blackboard Jungle. Many cite this film, more specifically the opening titles sequence that features Haley’s classic tune, as the moment rock and role was born, the catalyst by which it would take hold of an entire generation.

Blackboard Jungle made other headlines soon after its release. It was banned in cities like Memphis and Atlanta, with authorities accusing the movie of inciting riots among its mostly teen audiences. A few of these melees even spilt out onto the streets. In the United Kingdom, it was refused a certificate until major cuts were made. Not that the cuts mattered; there were riots in England as well.

Blackboard Jungle struck a nerve with kids looking for a voice of their own, and as a result many adults weren’t too keen on this black and white tale of rebellion and juvenile delinquency.

Now, decades after the trouble it caused, we can see what Blackboard Jungle was trying to do: bridge the gap between the generations by showing us a city school from a poor area of town, where kids join gangs just to feel safe in their own neighborhoods. And try as some teachers might, it was the kids who were usually in control.

Blackboard Jungle gets this point across - often and effectively - by focusing on one teacher who refused to give up, and would do everything in his power to reach his students.

Navy veteran Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) has just been hired as the new English teacher of North Manuel Trades, an inner-city high school legendary for its discipline problems. Dadier, whose wife (Anne Francis) is four months pregnant, believes he can make a difference at the school. His enthusiasm is soon tempered, however, when he butts heads with Gregory Miller (Sidney Poitier) and Artie West (Vic Morrow), two students who seem bound and determined to give the new teacher a hard time.

Dadier reaches out to Miller, who is smarter than he is letting on, while West and his cronies, including Belazi (Dan Terranova), Stoker (Paul Mazursky), and Morales (Rafael Campos), continue to make life difficult for Dadier and his fellow teachers, especially math teacher Mr. Edwards (Richard Kiley), who, like Dadier, got into teaching with the best of intentions, only to be pushed to the brink of quitting by West and the others.

But Dadier will not throw in the towel, leading to a battle of wills between he and West that could prove disastrous.

The script for Blackboard Jungle was penned by Evan Hunter, who drew from his own experiences working as a teacher at a city school (though, unlike his lead character, Hunter became so disillusioned that he quit after two months), and many of the confrontations between Dadier and his students, some just playful, others downright dangerous, bring a tension to the film that is all-encompassing.

Things get even rougher for Dadier when, on the first day of school, he rescues another teacher, Lois Hammond (Margaret Hayes), who was about to be raped by a student. Rumors circulate that Dadier beat the assailant senseless (in truth, the kid cut his own face when he tried jumping through a closed window to escape), and this draws the ire of every teen in his class.

The film’s most heartbreaking scene, though, occurs later, when Mr. Edwards brings in his jazz LP collection as a teaching tool. This collection featured some albums that were irreplaceable, only to be ruined when Artie West and his cronies, who don’t share Edwards’ love of music, stop by between classes.

Glenn Ford is damn good as the well-meaning but oft-frustrated Dadier, as is Sidney Poitier, in an early screen role as Greg Miller, an angry young man who, though belligerent, is the most intelligent member of the class. Also strong are Anne Francis as the concerned wife driven to despair by a vicious rumor that her husband may be having an affair with Lois Hammond; and Louis Calhern as veteran teacher Jim Murdoch, the most callous and sarcastic of Dadier’s co-workers, who has given up trying to teach, and now sees himself as a glorified babysitter.

And then there’s Vic Morrow. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the character of Artie West - and in turn the performance of Vic Morrow - that makes Blackboard Jungle such an unforgettable movie. West is always angry, always trying to get the upper hand on authority, whether in a classroom or a back alley (where, one night, he and the others jump Dadier and Edwards and beat them senseless).

West doesn’t talk as much as the other kids; when on-screen, he is usually brooding. The leader of his group, he refuses to let anyone, teacher or otherwise, take his “power” away from him, and it is he who at one point tries to get Dadier fired (by accusing him of bigotry) and starts the gossip about Dadier and Ms. Hammond.

Artie West is the villain of Blackboard Jungle, and who better to play him than one of the screen’s all-time great bad guys? From King Creole to The Bad News Bears, from Humanoids from the Deep to the ill-fated Twilight Zone: The Movie (during which Morrow and two child actors lost their lives following an on-set accident), Vic Morrow has been the guy you love to hate. Even when on the right side of the law, like he was in Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry, Morrow’s character has an edge, a sarcasm that makes him a thorn in the side of his superiors. With Artie West, Morrow delivered what is arguably the most vicious, the most detestable character of his career. And he played him brilliantly.

Though undeniably a teen-centric drama, there are portions of Blackboard Jungle that play like a thriller, sequences that will drag you to the edge of your seat and have you questioning why anyone would want to be a teacher in this school. Tough and unflinching, this film threw a spotlight on teen rebellion and let out a war cry, a warning to parents and authority figures across the U.S.

James Dean made rebellion look cool in Rebel Without a Cause. Based on the backlash it received, the kids in Blackboard Jungle stirred up the shit like nobody before them.

Rating: 9 out of 10

It could never take place

in most American towns –

But it did in this one

It is a public challenge

not to let it happen again”

When I think of the seminal Marlon Brando performances, a handful of roles leap immediately to mind. Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. Don Corleone of The Godfather. And, of course, Johnny, the rebellious biker in Stanley Kramer’s 1953 production of The Wild One.

A precursor to the biker exploitation films of the ‘60s and ‘70s, The Wild One is, indeed, wild, but it is also potently dramatic, with just a hint of romance. And, of course, there’s Brando, setting the screen on fire the moment he and his gang first ride into town.

After disrupting a motorcycle race, during which one of his gang steals the second-place trophy, Johnny Strabler (Brando) and his fellow Black Rebels make their way to a small California town. Frank Bleeker (Ray Teal), who owns the local bar / restaurant, welcomes Johnny and his gang, figuring they’ll spend plenty of money at his place. Johnny even falls for Frank’s niece, Kathie (Mary Murphy), only to seemingly lose interest when he discovers she’s the daughter of the weak-willed sheriff (Robert Keith).

An already tense situation escalates when rival biker gang The Beetles, led by the flamboyant Chino (Lee Marvin), turns up. Once the sun goes down, both the Black Rebels and Beetles start tearing up the place. As for Johnny, he can’t get his mind off of Kathie, who, it turns out, is as restless as he is.

Before the night is out, the bikers will face off against angry townsfolk, and odds are someone will end up dead.

In what is undoubtedly the film’s most iconic scene, Johnny and his gang are hanging out at Frank’s restaurant. A few of the bikers are dancing with local girls, one of whom, Mildred (Peggy Malay), noting the name of his gang, asks Johnny what it is he’s rebelling against. “What do ya got?” is his reply. It is an unforgettable exchange, but it’s Brando’s delivery of the line, punctuated by his cool, callous demeanor, that makes it so. Johnny doesn’t have a cause he’s fighting for, a credo or principle he lives by. He’s just looking to stir up trouble, which, from the looks of it, finds him everywhere he goes.

When he is talking with Kathie, though, we see a glimmer of something more in Johnny. At first, it’s straight-up physical attraction, but as he gets to know Kathie, he realizes her life isn’t any better than his. Her mother dead, her father considered a coward by most in town, she tells Johnny she’s been waiting for someone to take her away. We are never sure if it is love, or just convenience that attracts them to each other, but their scenes together are electric all the same.

The Wild One is, at times, a shocking motion picture, from the level of chaos that the bikers unleash on the town to the townsfolk’s violent reaction to it all. Yet it is the film’s extraordinary cast that impressed me most. Murphy delivers a solid performance as Kathie, with Marvin even stronger in his few scenes as the out-of-control Chino. But it is Brando, playing one of the screen’s most charismatic anti-heroes, who carries The Wild One to another level.

Rating: 9.5 out of 10

But The Pink Panther Strikes Again is also a mess. Its story is incohesive and bounces all over the place, from one subplot to the next, with no rhyme or reason. At times it feels more like a series of vignettes with a common theme than it does a feature film.

Rest assured, however, that these “vignettes” will have you rolling on the floor.

It has been three years since Chief Inspector Dreyfus (Herbert Lom) was committed to an asylum for the criminally insane. His former colleague – and the reason he lost his mind in the first place – Jacques Clouseau (Sellers) has since taken over as Chief Inspector of the Sûreté.

Given a clean bill of health by his doctors, Dreyfus was about to be set free. That is, until Clouseau came to visit him, an encounter that caused enough injury, and stirred up enough mayhem, to “break” Dreyfus once again. His hopes of a pardon dashed, Dreyfus escapes from the asylum, more determined than ever to kill Clouseau.

To this end, the former Chief Inspector:

1. Recruits the world’s most notorious criminals

2. Stages a daring bank robbery, and

3. Kidnaps renowned British physicist Hugo Fassbender (Richard Vernon) and his daughter (Briony McRoberts).

His plan: force Fassbender to build him a Doomsday machine, a laser so powerful it can wipe out an entire continent.

Once the weapon is completed, Dreyfus demonstrates its power by making the U.N. Building in New York vanish without a trace, then issues his demands to the world: turn Clouseau over within seven days, or he will destroy an entire city!

As for Clouseau, he is on the case, first teaming up with Scotland Yard to track down the kidnappers that abducted the Fassbenders, then setting his sights on finding Dreyfus’s secret hideout. But even if the blundering Clouseau does crack the case, odds are he will, in the process, do even more damage than the Doomsday Machine!

The Pink Panther Strikes Again gets off to a brilliant start with an hilarious pre-title sequence, during which a calm, sane Dreyfus is reduced to a quivering mass of nerves after spending just five minutes with Clouseau. There are other great moments as well, such as Clouseau returning home for the evening and getting into an epic battle with his servant Kato, not realizing that the escaped Dreyfus is in the apartment below, plotting to blow him to smithereens (a recurring gag involving Dreyfus drilling holes and watching Clouseau with a handheld periscope had my sides splitting).

But wait, there’s more.

Sellers is near flawless in the scene where Clouseau is questioning the household staff at the Fassbender Estate; and later, he takes a trip to Oktoberfest, where assassins from at least a dozen countries are trying to eliminate him (there’s a moment in a bathroom stall that is comedic gold).

Still, as good as Sellers is, one of the best things about The Pink Panther Strikes Again is that it gives Herbert Lom more screen time than he had in any of the previous movies, and his “lunatic Dreyfus” gets his share of laughs as well. The scene where he “tortures” Fassbender’s daughter is arguably one of the film’s most memorable.

There’s even a handful of amusing sequences set inside the White House, with President Gerald Ford (Dick Crockett), Henry Kissinger (Byron Kane), and the rest of the cabinet discussing how best to deal with the terror that Dreyfus has unleashed on the world.

Along with the comedy, The Pink Panther Strikes Again has a daring jailbreak set on a moving train; and a finale so elaborate it would have been at home in any of the James Bond movies.

That’s a lot to cram into one film, but it is still not the half of it, and herein lies the main issue I had with The Pink Panther Strikes Again. It’s just too much!

In addition to everything above, we get a few scenes in a gay bar, where the Fassbender’s butler, Jarvis (Michael Robbins), has a drag act (his singing voice was dubbed by Julie Andrews, Blake Edwards’ wife); as well as sequences set in Scotland Yard, where Superintendent Quinlan (Leonard Rossiter), who suffered an injury due to Clouseau’s incompetence, must decide whether or not to tell Paris their Chief Inspector is a moron.

There is even a poorly developed romance that blossoms between Clouseau and Russian assassin Olga Barlosova (Lesley-Anne Down), who was originally sent to kill him. And on top of all this, Omar Sharif turns up in a cameo… as an Egyptian assassin!

After doing a little research, I found out the film's issues likely developed during the scriptwriting phase. Initially, Blake Edwards and his co-writer Frank Waldman were going to turn Clouseau and The Pink Panther into a TV series. Eventually, that idea was dropped, and the script they had been compiling was turned first into The Return of the Pink Panther, then this movie.

The Return of the Pink Panther was at least somewhat structured, but by the time they got to The Pink Panther Strikes Again, they had to throw everything that was left into it, whether it made sense or not (there is no logical reason Clouseau went to Oktoberfest in the first place).

Apparently, there was even more! The first cut of this movie was three hours long (much of the excised footage would be re-used in the dismal 1982 failure Trail of the Pink Panther, a cheap attempt to keep the series going after Sellers passed away in 1980).

Not that any of this confusion matters in the end. You watch a Pink Panther movie to laugh, and when the chips are down, The Pink Panther Strikes Again works because it is flat-out hilarious.

Rating: 7 out of 10

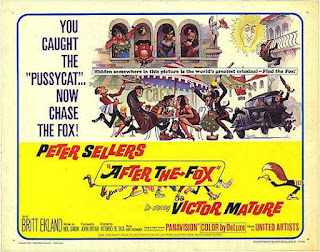

Directed by Vittorio de Sica (Bicycle Thieves, The Children are Watching Us).

Starring Peter Sellers (Dr. Strangelove, The Pink Panther).

Now, that’s a hell of a pedigree for any movie! And After the Fox is a hell of a movie. Not perfect, mind you, but with a manic energy that is infectious, and a story that’s just madcap enough to keep you laughing.

Master criminal Aldo Vanucci (Sellers), whose nickname is “The Fox”, has escaped from an Italian prison. After stopping home for a quick reunion with his bitter mother (Lydia Brazzi) and younger sister Gina (Britt Ekland), Vanucci goes into hiding, during which time he is contacted by fellow crook Okra (Akim Tamiroff).

Okra recently masterminded the theft of hundreds of gold bars in Cairo, and promises Vanucci half the loot if he can figure out a way to get that gold into Italy.

So, Vanucci devises an ingenious scheme. Posing as a film director named Federico Fabrizi, Vanucci will make a “movie” about a fortune in gold being smuggled into the country! He even manages to cast American star Tony Powell (Victor Mature) as the lead, much to the chagrin of Powell’s longtime manager Harry (Martin Balsam).

Aided by his gang, and with Powell in tow, Vanucci heads to the small seaside village of Sevalio, where the gold will be brought ashore. A fast talker, Vanucci convinces all of the locals, including the chief of police (Lando Buzzanco), to appear as extras.

With so many people helping, getting the gold loaded onto a truck will be a piece of cake. But two detectives (Tiberio Murgia and Francesco De Leone) are hot on his trail, meaning Vanucci will have to work fast if he is to have any chance of pulling off his elaborate scheme.

Having scored hits on Broadway with Barefoot in the Park and The Odd Couple, After the Fox was Neil Simon’s first original screenplay, and features much of his patented wit. But the movie is more a showcase for Peter Sellers’ unique brand of comedy than it is Simon’s. The first half of the film, which features Vanucci’s escape from prison and his attempts to suppress the movie star aspirations of his pretty sister, are funny enough. But it is the later scenes, where the character is in full “director” mode, that the actor’s talents shine brightest.

At one point, everyone in town is on the beach, waiting for the gold to arrive so they can shoot the “big finale”. Unfortunately, Okra learns the boat is running late, which means Fabrizi / Vanucci has to stall. With no idea what to do, he “shoots” an impromptu scene with Powell and Gina (who is posing as the film’s starlet) sitting at a dinner table, which has been hastily set up in the sand. When Powell asks what he and Gina are supposed to do in this scene, Vanucci says “do… nothing”. So, the two stare at one another.

Fabrizi follows this up by having them do “something”: he orders Powell and Gina to run through the entire town. When Powell asks who they’re running from, Vanucci replies “yourselves”. All at once, everyone witnessing these exchanges, Powell included, are convinced Fabrizi is an arthouse genius!

Also great is the film’s opening song, written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David (who scored a hit the year earlier with the title track for What’s New Pussycat) and featuring a duet between Peter Sellers and the rock group The Hollies!

A funny movie that takes potshots at egotistical directors (De Sica makes a cameo as himself, shooting a biblical picture in Egypt and telling his assistants the desert needs “more sand”), extreme fandom (Powell is mobbed by adoring fans everywhere he goes), and film snobs (there’s a late scene involving a movie critic that is hilarious), After the Fox is a ‘60s heist film and spoof of the cinema rolled into one. And despite a few slow spots in the middle, it does a damn good job with both.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

Y

ears before taking on three roles in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, Peter Sellers played a trio of characters in The Mouse That Roared, a 1959 comedy about a tiny country that declares war on the United States, and damn near comes out on top!

The Duchy of Grand Fenwick, an English-speaking dot on the map situated in the French Alps, has one chief export: wine! It seems their wine is a big hit in the United States, and this has kept the Duchy’s economy afloat for years. But when a vineyard in California knocks off their recipe, then charges less per bottle, Grand Fenwick finds themselves facing financial ruin.

In an effort to save his country, Prime Minister Count Rupert Mountjoy (Sellers) hatches a crazy scheme: declare war on the United States! Duchess Gloriana XII (also Sellers), the ruler of Grand Fenwick, and Benter (Leo McKern), leader of the opposition, have serious reservations, noting they do not have a prayer of winning such a war.

To their surprise, Count Mountjoy agrees with them. What’s more, he’s hoping they lose!

Familiar with U.S. history, Mountjoy believes that, once they are defeated, the United States will flood Grand Fenwick with millions of dollars in war reparations, at which point they will not only have secured their financial independence, but might also be able to afford that new coffee maker they have had their eye on!

Soon after mailing off their declaration to the U.S., Game Warden Tully Bascombe (Sellers, yet again) is named Field Marshall of the Grand Fenwick military, which consists of his second-in-command, Sergeant Will Buckley (William Hartnell), and twenty troops armed with bows and arrows. Boarding a small French steamer heading to New York, Tully and his platoon start their “invasion”, intent on surrendering the moment they hit U.S. soil.

Alas, things do not go according to plan. The day they arrive, New York is in the midst of a city-wide air raid drill, which means the streets are deserted. Then, while looking for a military H.Q., Tully and his men instead stumble upon Dr. Alfred Kokintz (David Kossoff) and his daughter Helen (Jean Seberg). Dr. Kokintz is the reason the city is practicing for an air raid, due to the fact he has just created the dreaded Q-Bomb, an atomic device powerful enough to destroy an entire continent!

Not only does Tully take the Dr. and his daughter prisoner, but he also confiscates the Q-bomb and, in the process, even captures a U.S. General (MacDonald Parke) and four New York policemen, taking all of them back to Grand Fenwick as his prisoners.

Their plan a shambles, Mountjoy and the others must scramble to get themselves out of this mess, and hopefully do so before the dreaded Q-bomb, which is highly volatile, explodes and takes all of Europe with it!

Directed by Jack Arnold and based on Leonard Wibberley’s novel of the same name, The Mouse That Roared is a very funny movie. The scenes in which Tully and his men are walking through the streets of an abandoned New York, wearing chain mail and carrying bows, is quite a sight. But it is when the “invasion” goes awry, and Tully returns a conquering hero, that things really spiral out of control. To get their greedy mitts on Kokintz’s Q-Bomb, practically every other country in the world lines up to support Grand Fenwick in their war against the United States, a war that Mountjoy and the others had hoped would be over already! There is also a romantic subplot, with Tully falling in love with Helen, whose initial annoyance at being taken prisoner eventually gives way to genuine affection.

Sellers, as expected, is quite good in all three roles. He is likable as the nebbish Tully, who makes a complete mess of things by winning the war; and even gets to camp it up a bit as the elderly Duchess. That said, it’s Sellers’s turn as Mountjoy that is his best, playing a devilishly clever character who is equally as conniving.

Yet as impressive as Sellers is, The Mouse That Roared would have been just as funny had another, or even three other actors, played his parts. This is a situational comedy, and it is what transpires over the course of the movie that has us laughing. Sure, Sellers is good. He always is. But unlike Dr. Strangelove, where he shines and even steals the film’s later scenes as the title character, it’s the story in The Mouse That Roared, and not Sellers’ patented madcap physical humor, that keeps us in stitches.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

Angered by a trade embargo imposed on them by the U.S., Japan enters into an alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in September of 1940, thus becoming one the Axis Powers. With the threat of war looming heavily, Admiral Husband Kimmel (Martin Balsam) of the Navy and the Army’s General Walter Short (Jason Robards), both stationed in Pearl Harbor, issue a number of alerts to keep the troops on their toes.

As Japanese Ambassador Nomura (Shogu Shimada) and the U.S. Secretary of State (George MacReady) work towards a peaceful resolution, Japan’s navy, under the command of Admiral Yamamoto (So Yamamura), is preparing for a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, to cripple the American Navy. Assisted by Commander Minoru Genda (Tatsuya Mihashi) and Lt. Cmdr. Mitsuo Fuchida (Takahiro Tamura), Yamamoto puts his plan into motion, choosing the morning of Sunday, Dec. 7 as the best time to launch the attack.

Striving for an accurate portrayal of events both before and during the bombing on Pearl Harbor, Tora! Tora! Tora! spends its entire first half setting up the attack, from the growing tension between the two countries to their armies and navies preparing for the inevitability of war. Featuring a number of high-level meetings between bureaucrats and military commanders, the first half of Tora! Tora! Tora! has its moments; I especially liked the scenes where U.S. Intelligence was working feverishly to intercept and decode messages sent to the Japanese Ambassador. Unfortunately, there aren’t enough of these moments, and for a time the movie plods along at a slow pace. I do applaud the filmmakers for their historical accuracy, but there are reasons why most war movies don’t dedicate a lot of screen time to closed-door meetings! That said, the early Japanese segments of Tora! Tora! Tora! are livelier, in part because the military and their preparations are front and center, but I also think Masuda and Fukasaku infuse these sequences with an energy that isn’t present, at least initially, in the American scenes.

It’s during the second half of Tora! Tora! Tora! that the movie really comes alive, from the Japanese planes taking off to the attack itself, which, like the rest of the film, leans towards historical accuracy. Simultaneously exciting and heartbreaking, the bombing of Pearl Harbor is brilliantly brought to life, and stands as one of the best depictions of this tragic day in American history.

While there are no big-name stars in Tora! Tora! Tora!, the cast does a fine enough job, especially Robards as the cantankerous General Short; E.G. Marshall as Lt. Col. Bratton, Chief of Military Intelligence (he’s the first to raise concerns of a possible attack); and So Yamamura as the apprehensive Yamamoto, who fears that, even if the attack is successful, all Japan will have done is “Awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve”.

Though not consistently exciting, Tora! Tora! Tora!, by telling the story of Pearl Harbor from both sides of the conflict, has enough going for it to make it worth your time.

Rating: 6.5 out of 10

Based on James Jones’ 1962 novel of the same name, The Thin Red Line centers on the 1942 battle of Guadalcanal, when U.S. marines took on the Imperial Japanese army. With a star-studded cast, the movie takes us from the initial days of the campaign, when the marines, under the leadership of Lt. Col. Gordon Tall (Nick Nolte), found themselves outmatched and outnumbered by the Japanese. As Col. Tall, ignoring the odds against them, demanded that his troops press on, his subordinates, including Capt. James Staros (Elias Koteas), Lt. John Gaff (John Cusack), and Sgts. Edward Welsh (Sean Penn), Maynard Storm (John Savage), and Brian Keck (Woody Harrelson) were locked in the fight of their lives, losing troops by the dozens.

The marines would eventually take a vital hill as well as the airfield that was the operation’s ultimate goal, but even then, the battle was far from over.

Along with the actors already mentioned, The Thin Red Line features Jim Caviezel as Pvt. Witt, Ben Chaplin as Pvt. Bell, Adrien Brody as Cpl. Fife, Jared Leto as 2nd Lt. William Whyte, Tim Blake Nelson as Pvt. Tills, John C. Reilly as Sgt. Storm, and Nick Stahl as Pvt. Beade. Also turning up in cameos are John Travolta as Brig. Gen. Quintard and George Clooney as Capt. Bosche, with Mirando Otto appearing in several flashbacks as Pvt. Bell’s wife.

Now, that’s one hell of a cast, and if I’m being honest, it is a bit distracting each time a big star appears on-screen. But Malick balances his actors perfectly, giving each their moment to shine while also moving the story along at a brisk pace.

Some get more screen time than others. As the movie opens, Jim Caviezel’s Pvt. Witt, who has gone AWOL, is living among the Melanesian natives of the South Pacific. He is eventually found and taken into custody, at which point his direct superior, Penn’s Sgt. Welsh, removes him from combat duty and orders him to act as a stretcher bearer during the Guadalcanal campaign. Pvt. Witt and Sgt. Welsh will share several scenes together, with their differing philosophies taking center stage. Pvt. Witt is a firm believer in the afterlife, while Sgt. Welsh, who has seen his share of horrors, cannot fathom a world beyond the one he knows.

Their spiritual debates are but one of the film’s many introspective moments. Time and again, Pvt. Bell, played wonderfully by Ben Chaplin, reflects on the love he has for his wife, and the hope that they will one day be reunited. “Why should I be afraid to die?”, Bell says, narrating his own flashback, “I belong to you. If I go first, I'll wait for you there, on the other side of the dark waters”.

And yet, even with its meditative tone, The Thin Red Line is a highly effective war film, conveying the chaos of warfare and never shying away from the carnage. Several characters are killed over the course of the movie, and there are moments, especially during the initial battles, that are as tense as anything you’d find in Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan. It is both a nerve-racking World War II movie and a Terrence Malick film through and through, and this duality is what makes The Thin Red Line such a rewarding experience. It is not to be missed.

Rating: 9.5 out of 10